quantum key-exchange

The perfect cryptographic primitive—does it exist?

You’ve probably heard of the one-time pad: a cipher infamous for its drawbacks almost as much as for its absolute perfection. It is an example of an information-theoretic secure cipher—one that is mathematically proven to be unbreakable even in the face of infinite computing power.

So why don’t we use it? Well, the drawbacks of the scheme are in the key-exchange. The OTP requires a truly random key that is as long as the plain-text and that can only be used once. So if you want the benefits that it provides, you’re pretty much resigned to meeting up in person and exchanging an SSD full of random bytes every so often.

Basically, all you’re doing is having a face-to-face meeting delayed until after you meet. Suffice it to say, this is a little inconvenient.

But it is necessary, right? I mean, if you use conventional key-exchange using RSA or ECC, you’d defeat the purpose of using an information-theoretic secure cipher. But what if there existed another way of exchanging keys, one that was also perfect?

Well, there is: quantum key-distribution.

I’m not just talking perfect as in infinite computing power cannot touch it, I’m talking so perfect that no one can even attempt to intercept the transmission without being detected. This is guaranteed by the no-cloning theorem, so if this turns out to be wrong, we would have to reconsider our most fundamental beliefs about the nature of the universe—not to mention that it would fly in the face of the most precise and accurate experimental tests in all of science.

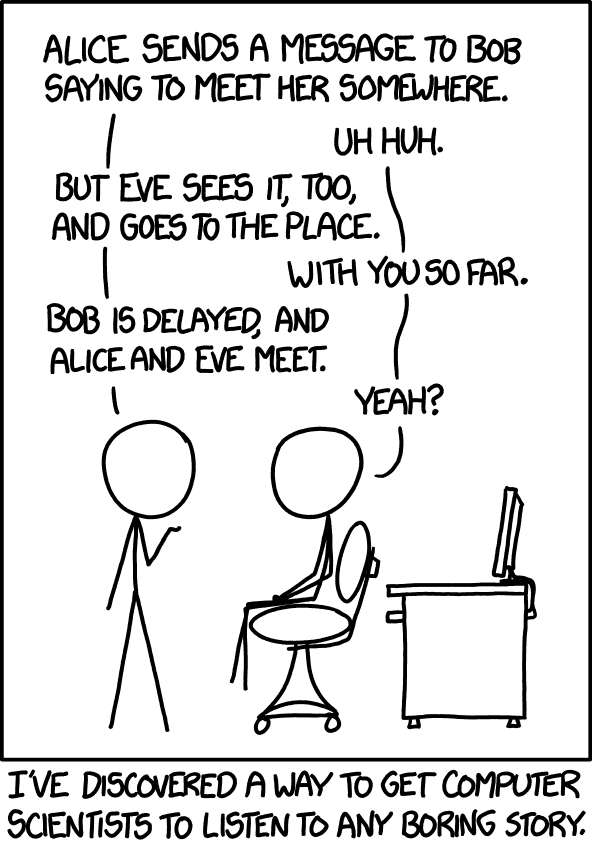

Consider two people—Alice and Bob—attempting to communicate securely, and a third person—Eve—attempting to intercept their communications. They have access to two insecure channels: a conventional one for bits, and a quantum one for qubits.

Alice has the option of using two different polarisation basis—rectilinear and diagonal—using which she can send either 0 or 1. She arbitrarily decides that a 1 encoded in the rectilinear basis will be vertically (0°) polarised, a 1 encoded in the diagonal basis will be polarised at 45°, and so on. This is summarised in the table:

| Basis | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Rectilinear (+) | 90° | 0° |

| Diagonal (x) | 135° | 45° |

She informs Bob of this scheme through the conventional channel, and now they are ready to exchange keys.

Alice begins by generating cryptographically-secure random pairings of bits and basis—huge amounts of them. For example, .

One at a time, she encodes the bits in their associated basis and sends the resulting polarised photons to Bob through the quantum channel. Now, the way this works is that any party that wishes to read these incoming qubits cannot tell which basis they were encoded in—so they just guess. But there’s another catch: if they measure the qubit in the wrong basis, the reading they get is purely random, and the qubit is destroyed in either case.

If you’re paying attention, you will have realised the importance of that property. Eve cannot read any qubits and remain undetected, as any attempted measurement on her part will result in the destruction of the original data.

After Alice has sent all of her data, Bob publicly informs Alice of his choices of basis for each bit. Alice then replies with the actual basis and they both discard any bits where Bob guessed incorrectly. Statistically, Bob will guess correctly around 50% of the time, so they are left with around half of the total bits sent.

Now all they need to do is check if Eve attempted to eavesdrop on the key-exchange. They take a random subset of bits from the exchanged data and compare them over the conventional channel. If this subset matches, they know—with a high degree of confidence—that their exchange is secure. Otherwise, they discard the data and start again.

This setup is provably secure against passive eavesdropping, but what about an active man-in-the-middle attack? Say Eve is able to modify the data sent on each communication channel. On the quantum channel this isn’t a problem—Eve cannot perform an MITM attack without being detected—but on the conventional channel we have to think about some kind of authentication.

Luckily, there exists an authentication scheme that provides unconditionally-secure authentication—similar to the OTP. It was invented in the late 70’s by J. Lawrence Carter and Mark N. Wegman, and so is commonly referred to as Wegman-Carter authentication. Without getting into the specific details—this post is meant to be about quantum key-exchange—it allows us to turn a pre-shared secret into a message authentication code that we can include with our messages.

So, to authenticate the conventional channel, on the first exchange Alice and Bob simply agree on a small, cryptographically-secure key in advance. They use this key for Wegman-Carter authentication and save a subset of the exchanged bits for use as the key in the next exchange. This way, both active and passive attacks by Eve are impossible without detection, and the OTP is back in the game.

{home : : subscribe with rss/atom}- 2024-07-23 : : how monzo generates sensitive secrets for its banking platform

- 2022-02-15 : : securely delegating trust with signatures and key management

- 2020-12-16 : : rosen: censorship-resistant proxy tunnel

- 2020-02-20 : : plausibly deniable encryption

- 2019-07-20 : : memory retention attacks

- 2019-07-18 : : encrypting secrets in memory

- 2019-06-27 : : mutable strings in go

- 2019-05-02 : : to slice or not to slice

- 2017-08-03 : : memory security in go