plausibly deniable encryption

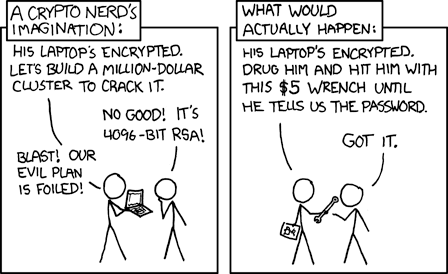

It is safe to assume that in any useful cryptosystem there exists at least one person with access to the key . An adversary with sufficient leverage can bypass the computational cost of a conventional attack by exerting their influence on this person.

The technique is sometimes referred to as rubber-hose cryptanalysis and it gives the adversary some serious creative freedom. The security properties of the cryptosystem now rely not on the assumed difficulty of mathematical trapdoor functions but on some person’s tolerance to physical or psychological violence. A thief knows that pointing a gun will unlock a safe much faster than using a drill. An adversarial government will similarly seek information using torture and imprisonment rather than computational power.

Many countries have key-disclosure legislation. In the United Kingdom, RIPA was first used against animal-rights activists to unlock data found on machines seized during a raid on their homes. The penalty for refusing to hand over key material is up to two years in prison.

Say Alice has a cryptosystem whose security properties rely on the secrecy of the key . To defend against attacks of this form Alice needs some way to keep a secret. She could,

- Claim that is not known. This includes if it has been lost or forgotten.

- Claim the ciphertext is random noise and so is not decryptable.

- Provide an alternate key under which decryption produces a fake plaintext.

Suppose Mallory is the adversary who wants and suppose Alice makes a claim in order to avoid revealing . Defining success can be tricky as Mallory can ultimately decide not to believe any claim that Alice makes. However we will simply say Mallory wins if she can show and therefore assert that Alice has access to and is able to provide it. So for Alice to win, must be unfalsifiable and hence a plausible defence.

As a side note, if Alice knows and can demonstrate whereas Mallory cannot, then clearly she is missing some necessary information. Kerckhoffs’s principle says that the security of a cryptosystem should rely solely on the secrecy of the key , so in general we want proving to require knowing .

We will ignore weaknesses related to operational security or implementation. For example if Mallory hears Alice admit to Bob that she is lying or if she finds a fragment of plaintext in memory then Alice has lost. However these situations are difficult to cryptographically protect against and so we assume security in this regard.

Pleading ignorance (1) of is an easy strategy for Alice as it leaves little room for dispute and it can be deployed as a tactic almost anywhere. Mallory must show that is known and this is difficult to do without actually producing it. Perhaps the key was on a USB device that has been lost, or was written down on a piece of paper that burned down along with Alice’s house. Mere forgetfulness however implies that the data does exist and the only barrier to retrieving it is in accessing Alice’s memories. This may not be satisfactory.

Asserting the non-existence (2) of the ciphertext is equivalent to claiming that does not exist and so cannot be disclosed. Plausibility comes from the fact that ciphertext is indistinguishable from random noise. This means that given some potential ciphertext an adversary cannot say if is uniformly sampled or if is a valid message encrypted under some key . To prove that is not random noise Mallory must produce and compute , which is assumed to be infeasible.

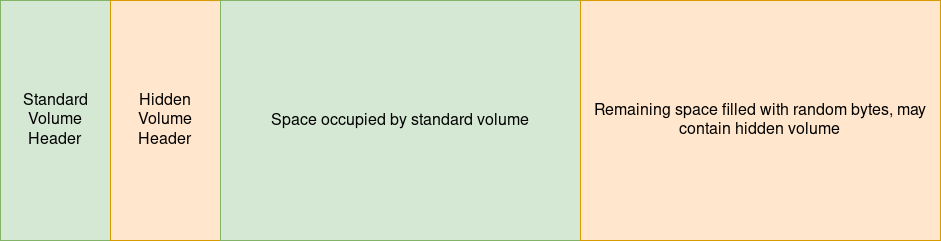

TrueCrypt and VeraCrypt allow the creation of hidden volumes and hidden operating systems. The idea is that an ordinary encrypted volume will have unused regions of the disk filled with random data, and so a hidden volume can be placed there without revealing its existence.

On-disk layout of an encrypted VeraCrypt volume.

Suppose we have a boot drive with a standard volume protected by the key and a hidden volume protected by the key . The existence of the unencrypted boot-loader reveals the fact that the standard volume exists and so Mallory can confidently demand its key. Alice may safely provide Mallory with thereby revealing the innocuous contents of the standard volume. However when Alice enters , the boot-loader fails to unlock the standard region so instead it tries to decrypt at the offset where the hidden volume’s header would reside. If the hidden volume exists and if the provided key is correct, this operation is successful and the boot-loader proceeds to boot the hidden operating system.

This is an example of providing a decoy decryption (3) but you may notice that Alice also had to claim that the remaining “unused” space on the drive is random noise (2) and not valid ciphertext. The necessity of a secondary claim is not a special case but a general property of systems that try to provide deniability in this way.

Providing a plausible reason for the existence of leftover data can be tricky. VeraCrypt relies on the fact that drives are often wiped with random data before being used as encrypted volumes. In other situations we may have to be sneakier.

This strategy does have some practical limitations. If the volume hosts an operating system, the innocuous OS has to be used as frequently as the hidden one to make it seem legitimate. For example if Alice provides the key and Mallory sees that the last login was two years ago, but she knows that Alice logged in the day before, then Mallory can be pretty sure something is off. Also consider what happens if Mallory sees a snapshot of the drive before and after some data is modified in the hidden volume. She then knows that there is data there and that it is not simply the remnants of an earlier wipe.

The Dissident Protocol

Imagine a huge library where every book is full of gibberish. There is a librarian who will help you store and retrieve your data within the library. You give her a bunch of data and a master key. She uses the master key to derive an encryption key and a random location oracle. The data is then split into book-sized pieces, each of which is encrypted with the derived key. Finally each encrypted book is stored at a location provided by the oracle.

More formally, assume “library” means key-value store. Consider a key-derivation function and a keyed cryptographic hash function , where is the key space. We also define an encryption function and the corresponding decryption function , where and are the message space and ciphertext space, respectively.

Alice provides a key which Faythe uses to derive the sub-keys . Alice then provides some data which is split into chunks , where every is padded to the same length. Finally, Faythe stores the entries in the key-value store.

For decryption, again Alice provides the key and Faythe computes the sub-keys . She then iterates over , retrieving the values corresponding to the keys and computing , stopping at where the key-value pair does not exist. The plaintext is then , after unpadding each .

Some extra consideration has to go into integrity and authentication to prevent attacks where the data Alice stores is not the data she gets back out. We leave this out here for simplicity’s sake.

Suppose the library contains books in total. Mallory cannot say anything about Alice’s data apart from that its total size is less than or equal to the amount of data that can be stored within books. If, under duress, Alice is forced to reveal a decoy key that pieces together data from books, she needs some way to explain the remaining books that were not used. She could claim that,

- The key for those books has been lost or forgotten.

- They are composed of random noise and so cannot be decrypted.

- They belong to other people and so the key is not known to her.

This will look mostly familiar. Alice is trying to avoid revealing her actual data by providing a decoy key that unlocks some innocuous data. She then has to make a secondary claim in order to explain the remaining data that was not decrypted under the provided key.

Claiming ignorance (A) has the same trivial plausibility argument and practical limitation as before (1).

Asserting that the leftover books are composed of random bytes (B) requires an explanation for how they came to be there. She could say simply that she added them but this is a can of worms that we want to keep closed. If some software implementation decides how many decoy books to add, it would necessarily leak information to Mallory about the expected frequency of decoys. This value can be compared with Alice’s claim of decoys to come up with an indicator of whether Alice is lying.

We have the same problem if the frequency is decided randomly as the value would have to lie within some range. We can get around this by asking Alice herself to decide the frequency, but this is messy and humans are bad at being unpredictable. In any case, this strategy boils down to Alice claiming “I added decoy entries explicitly in order to explain leftover data”, and this would rightly make an adversary extremely suspicious.

A better way to utilise B is for Faythe to replace books that are to be deleted with random data instead of removing them outright. Then Alice can claim that the remaining books have been deleted and therefore the data no longer exists and cannot be decrypted. This way potentially any number of leftover books can be easily explained, but it does mean that the size of our library will only increase over time.

Claim C is new and has some appealing properties but it can’t be used on a personal storage medium—like Alice’s laptop hard drive—as there is unlikely to be a plausible reason for other people’s data to be there. Imagine instead that the “library” is hosted on a service shared by multiple people. Then it is easy for Alice to claim that the remaining entries are not hers. Mallory would need leverage over every other person using the service in order to disprove Alice’s claim. Such a service has to be carefully designed however. For example if it stored how much space Alice is using then this value can be compared with Alice’s claim and Mallory wins.

There are some drawbacks of this scheme. There is an overhead in storing data in discrete, padded chunks. Modifying data in a non-trivial way may be expensive. Overwriting entries instead of removing them uses up storage space that is “wasted” in the sense that it does not hold any useful data. In designing this protocol what I have found is that we have to be extremely careful to avoid losing our deniability. Any implementation has to be verified to ensure that it does not fall short in this regard.

However we now have something that lets you have an arbitrary number of independent “folders” stored amongst numerous indistinguishable packets, with an adversary being unable to infer any information other than the maximum size of the stored data. This is a powerful property but it should be considered as part of the whole picture including your threat model and usability requirements.

{home : : subscribe with rss/atom}There is an experimental client implementing the spirit of this protocol here. As of the time of writing, it is not ready for serious use. However there are some exciting ideas I have for making this into a production ready and usable client in the (hopefully) near future.

- 2024-07-23 : : how monzo generates sensitive secrets for its banking platform

- 2022-02-15 : : securely delegating trust with signatures and key management

- 2020-12-16 : : rosen: censorship-resistant proxy tunnel

- 2019-07-20 : : memory retention attacks

- 2019-07-18 : : encrypting secrets in memory

- 2019-06-27 : : mutable strings in go

- 2019-05-02 : : to slice or not to slice

- 2017-08-03 : : memory security in go

- 2017-07-30 : : quantum key-exchange